Goldman Sachs - Blackpilled - 'Lost decade' risk

The S&P 500 has undoubtedly been a source of long-term wealth. Over the past four decades, asset prices experienced one of the most significant growth periods in financial history. More than 90% of the price appreciation in traditional equity-bond portfolios over the last 90 years occurred between 1984 and 2007.

Domestic equities contributed 94% of the returns, while bonds accounted for 76% of the profits, earning 15 times more than during any other period. Any strategy that heavily weighted stocks and bonds performed exceptionally well during this unique time.

The driving force behind this was a once-in-a-generation demographic surge of 76 million baby boomers.

Entering the market in the 1980s, they earned, spent, and saved, creating a massive influx of capital just as technology and globalization were taking off and interest rates peaked at 19%.

Over the past 44 years, this wave of capital, combined with globalization, falling interest rates, and lower taxes, fueled unprecedented procyclical growth in traditional asset prices.

However, it's unrealistic to expect similar returns over the next 40 years, especially from bonds, as yields are unlikely to decline the way they did in the past 45 years. So, we must ask ourselves whether such performance is repeatable.

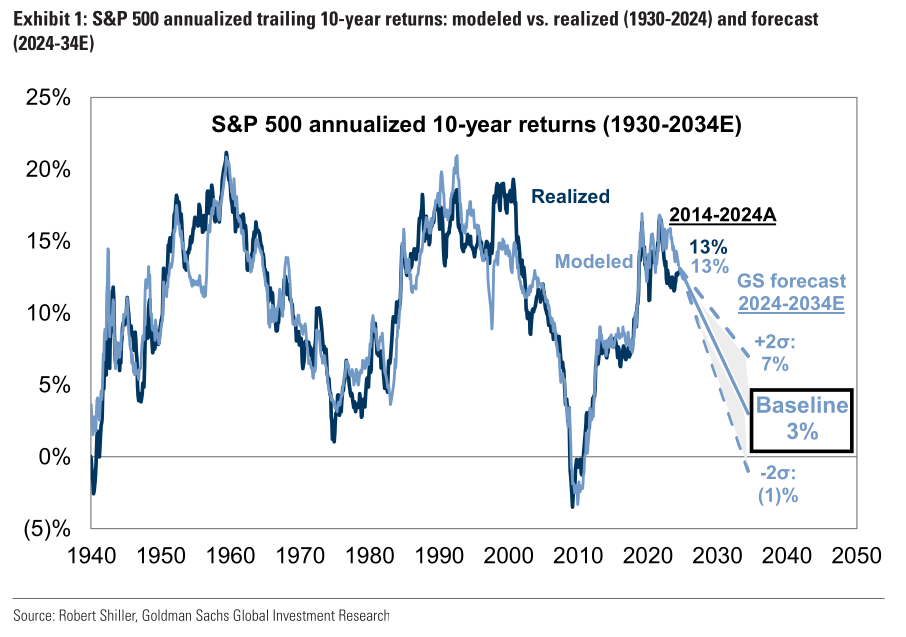

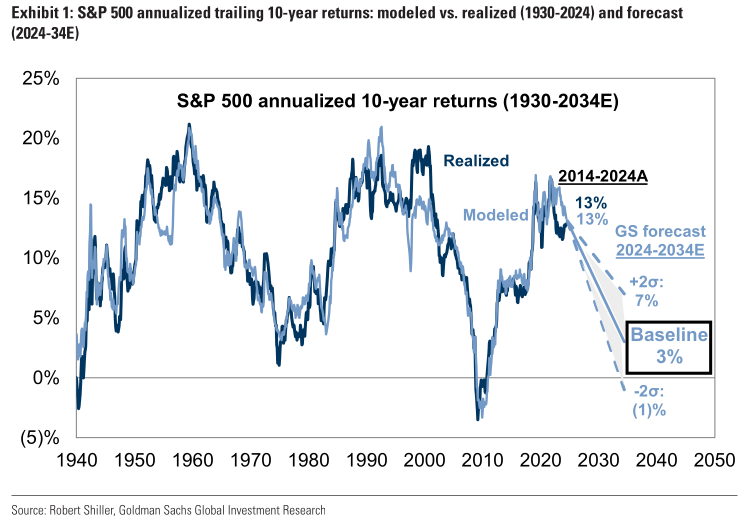

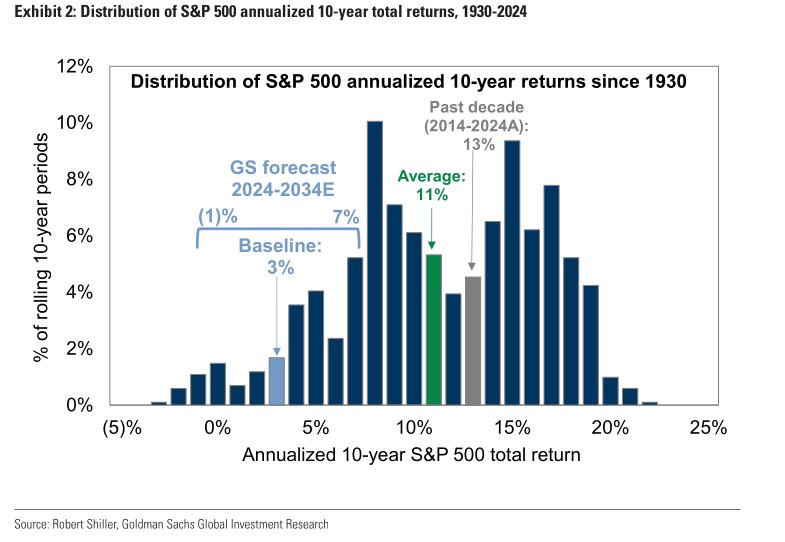

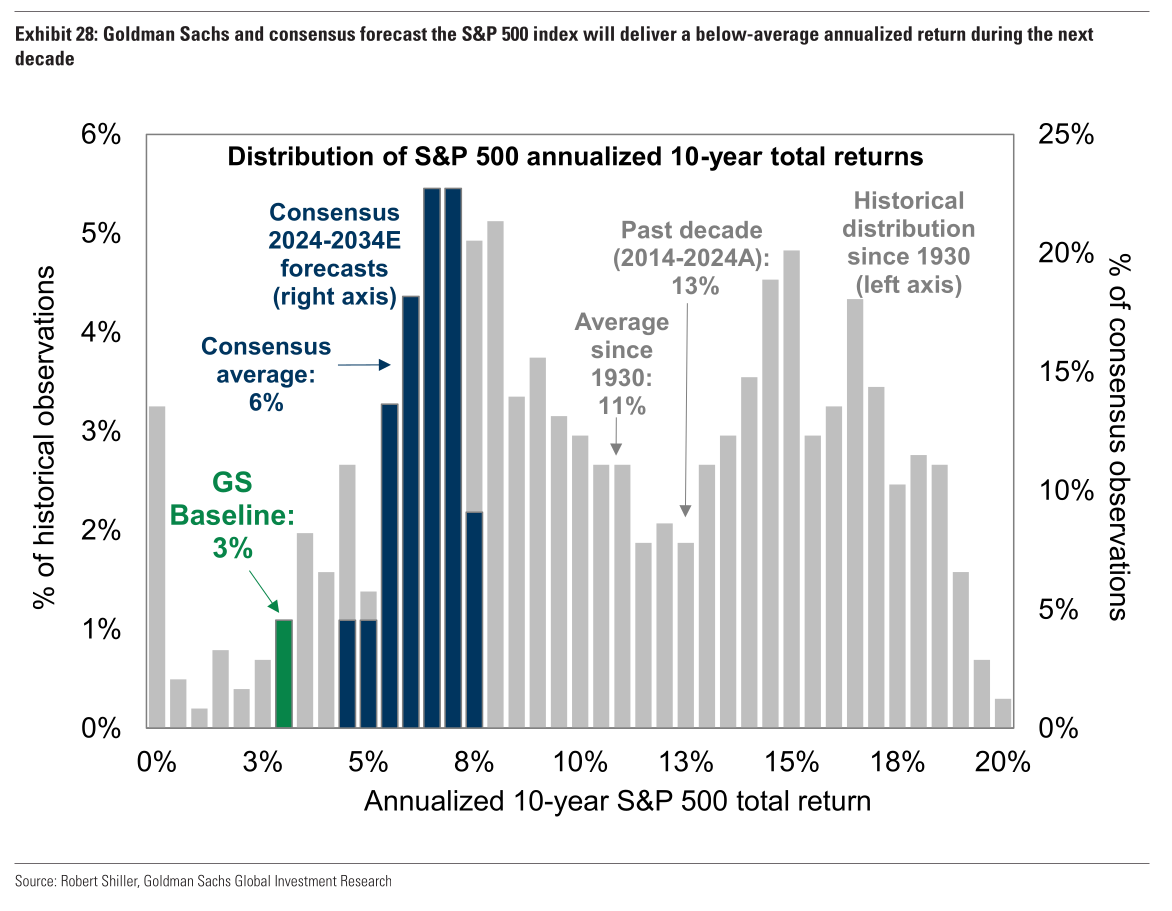

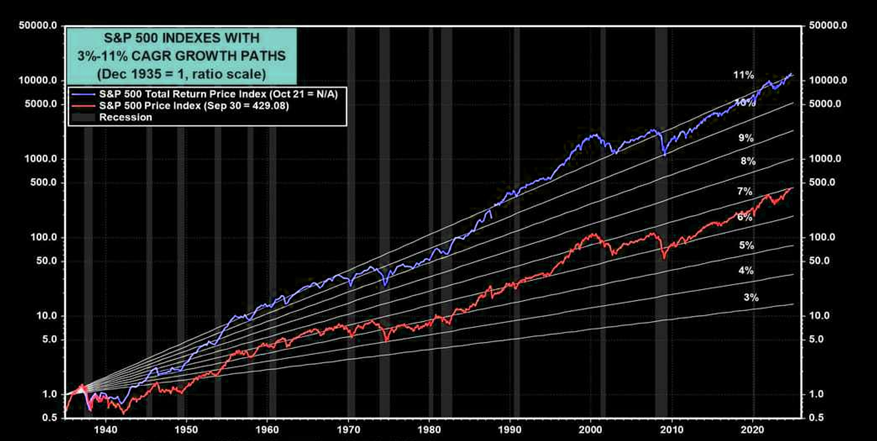

Over the past decade, the S&P 500 delivered an impressive 13% annualized total return, surpassing its long-term average of 11%.

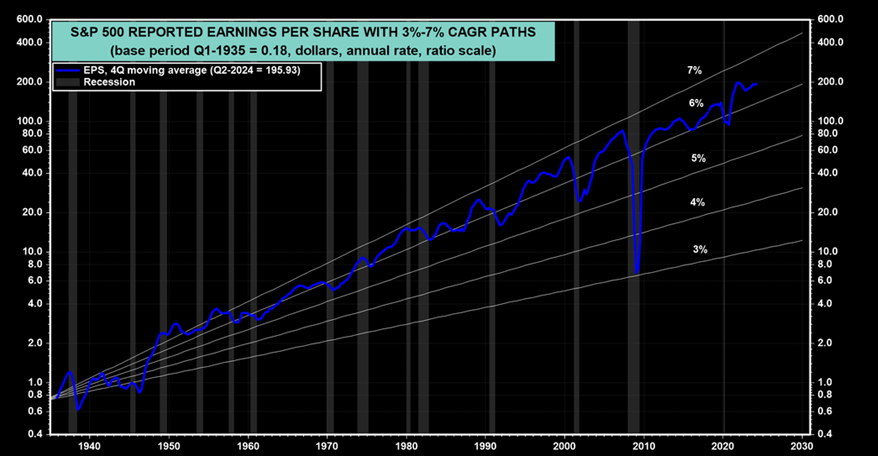

This translates to a cumulative total return of 233% from 2014 to 2024. Dividends contributed significantly, accounting for 54% (roughly one-quarter) of this total return. The remaining 178% of price appreciation was primarily driven by earnings growth (127%) and valuation expansion (52%).

If we exclude this once-in-a-generation period of asset price appreciation, typical portfolio returns could fall to just 4-5% per year. Without a repeat of that extraordinary period of growth, there may be a need for a bailout of entitlement programs that could surpass what we saw during the great financial crisis.

Goldman Sachs published their report called "long-term return Forecast for US Equities to

incorporate the current high level of market concentration" a few days ago

Now, you may have seen some tweets on Twitter coming from Tradfi Twitter, where they post this chart. Which is a concerning chart but also cherry-picked. So let's go over their report together. Page by page without leaving anything out

Of course, there is more in the world than just equities and fixed income. Gold and Silver have proven themselves to be reliable over hundreds of years. I would recommend to always have 19-20% of your portfolio in Gold. iShares Gold ETF or

Anyway, what is driving these returns? Earnings grew at an annualized rate of 7%, supported by increased sales, higher operating margins, and favorable tax policies. Meanwhile, the forward price-to-earnings (P/E) multiple increased from 16x to 22x, reflecting market optimism and valuation growth.

Can we expect this trend to continue over the next decade?

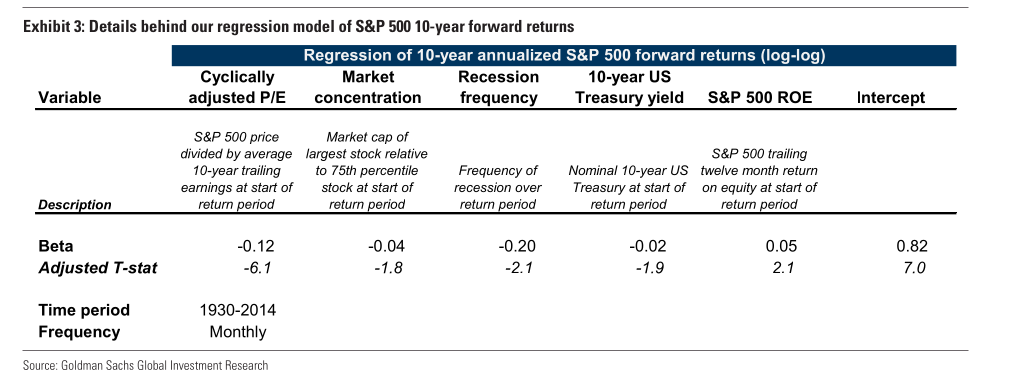

Forecasting the next decade is always fraught with uncertainty, but Goldman Sachs provides a model that uses five key variables to project future returns:

- Valuation: The S&P 500’s cyclically adjusted P/E (CAPE) multiple, which takes into account average earnings over a 10-year period, helps gauge whether the market is over or undervalued.

- Economic Fundamentals: The frequency of economic contractions (recessions) plays a crucial role in shaping long-term returns.

- Interest Rates: The 10-year U.S. Treasury yield is a benchmark for risk-free returns and a key factor influencing equity valuations.

- Market Concentration: The ratio of the market cap of the largest stock to the 75th percentile stock measures the dominance of large-cap companies, which can impact future returns.

- Profitability: The return on equity (ROE) of the S&P 500 reflects the efficiency with which companies generate profits.

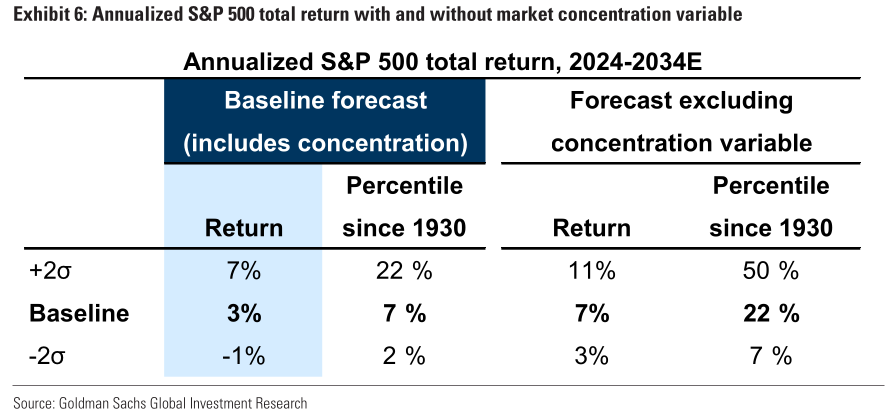

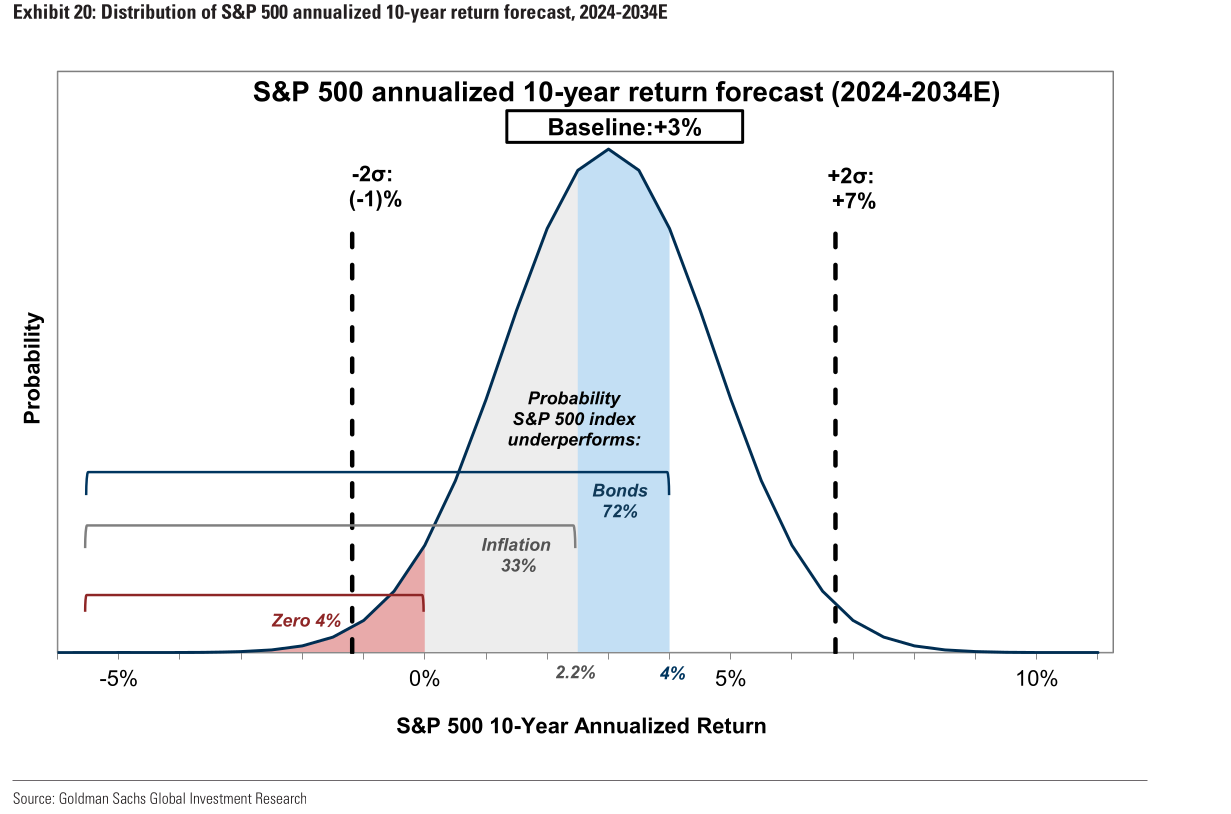

Based on this model, Goldman Sachs forecast a nominal annualized total return of 3% for the SPX500 over the next decade, which is well below the historical average. That would place the projected return in the 7th percentile of all 10-year periods since 1930

The Distribution of Returns

When we look at the historical distribution of 10-year returns of the SPX500, we see that returns are not symmetrically distributed. Instead, the distribution has a left skew with poor returns, such as the 1930s, 1960s, and early 2000. On the flip side, stronger returns during the 1940s, 1950s and 1980s

The distribution reflects 2 important statistical features of equity returns: negative skewness (the likelihood of poor returns higher than what a normal distribution would look like) and excess kurtosis (fat tails). This means that extreme outcomes, both positive and negative, are more common than in a normal distribution.

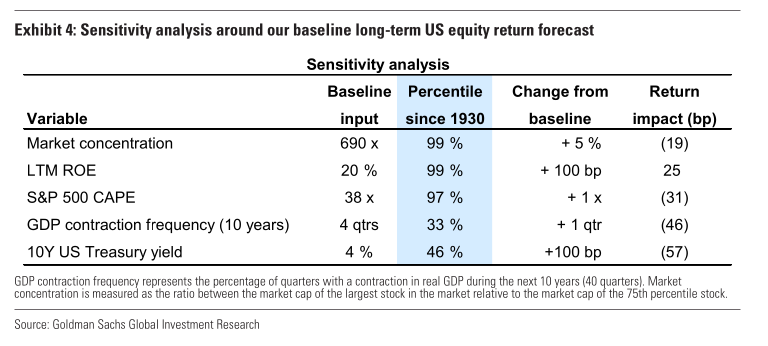

While the baseline forecast suggests a 3% annualized return, there is a range of potential outcomes. A sensitivity analysis shows how different starting conditions might affect the return outlook later.

Valuation (CAPE): A 1-point change in cyclically adjusted P/E multiple could move the baseline return forecast by 31 basis points. Given that CAPE is currently elevated, any downward revision can have a large impact on returns

Market concentration: Today's market is highly concentrated, with the largest stocks representing an outsized share of total market capitalization. A 5% change in market concentration would shift the forecast by 20 basis points.

Interest Rates: The 10-year U.S. Treasury yield also plays a role. A 100 basis points increase in Treasury yield will reduce the return forecast by 57 basis points.

Valuations

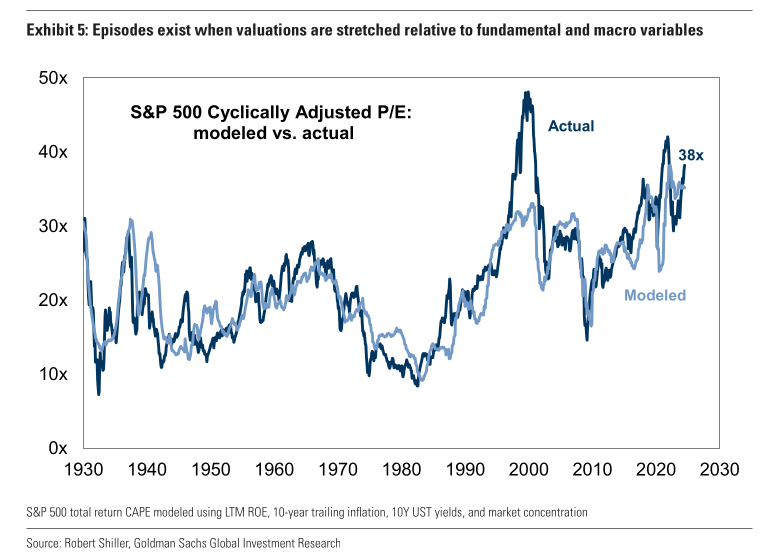

Valuation is central in forecasting future returns for the S&P500 and understanding the implications.

One of the core insights from historical data is that high starting valuations tend to be associated with lower forward returns, especially over longer time horizons. The relationship between starting valuation and forward 10-year returns is stronger than that for shorter horizons like 1 or 5-year return periods.

Right now, the CAPE ratio stands at 38x, placing it at the 97th percentile of historical valuations since 1930. The elevated level might indicate a potential headwind for future returns, contributing to Goldman Sachs' conservative baseline forecast of 3% annualized nominal returns through 2034.

The CAPE ratio adjusts for earnings cyclicality, making it a more reliable measure of market valuations over time. As we see it today, a high CAPE implies that the market is priced richly relative to its long-term earnings potential. When valuations are stretched, future returns often face downward pressure unless profitability growth or macroeconomic conditions improve to justify the premium investors pay.

However, valuation alone can sometimes send misleading signals; it's important to view CAPE in the context of the market's fundamentals and structural factors, such as corporate profitability and interest rates.

Profitability: Measured by the S&P500 trailing four-quarter returns on equity (ROE), profitability is important to gauge how efficiently companies generate profits. High profitability can justify elevated valuations, as investors are willing to pay more for companies that deliver strong returns on capital. In today's market, profitability remains strong, helping to temper some of the high risk associated with the high CAPE ratio.

Interest rates: The nominal yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond serves as a benchmark for the discount applied to future corporate profits. Lower interest rates reduce the discount rate, marking future earnings more valuable and supporting higher equity valuations. Right now, interest rates remain relatively low, meaning the high CAPE ratio is less alarming than it would be in a higher interest rate environment.

So are valuations too high?

Although the CAPE ratio is historically high, there is room for nuance when viewed in context against today's interest rate and profitability. While it’s important to approach current valuations cautiously, they are not overly alarming relative to historical episodes. That said, starting from such elevated levels suggests a more challenging road ahead, which is why the forecasted returns are at the lower end of the historical distribution.

Also, if you are a premium member, join Discord for full benefits.

Yes, options data, such as dark pools, options gamma, unusual flow, etc., are also included.

The article does not end here; scroll down to continue reading

Market Concentration

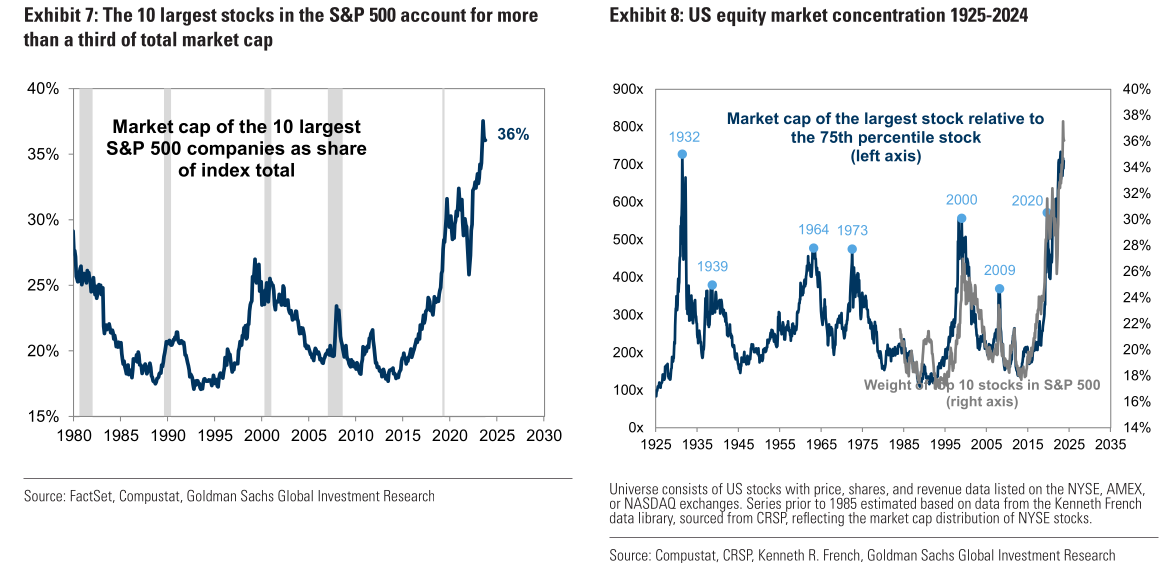

Market concentration refers to the degree to which a small number of companies dominate a large share of the overall market. In the case of the S&P500, today's market concentration is driven by the dominance of mega-tech tech companies, which amassed an enormous market share due to their profitability, scalability, and competitive advantages.

Market concentration has recently surged to a multi-decade high. We have previously identified seven other instances when concentration rose sharply and peaked, including 1932, 1939, 1964, 1973, 2000, 2009, and 2020.

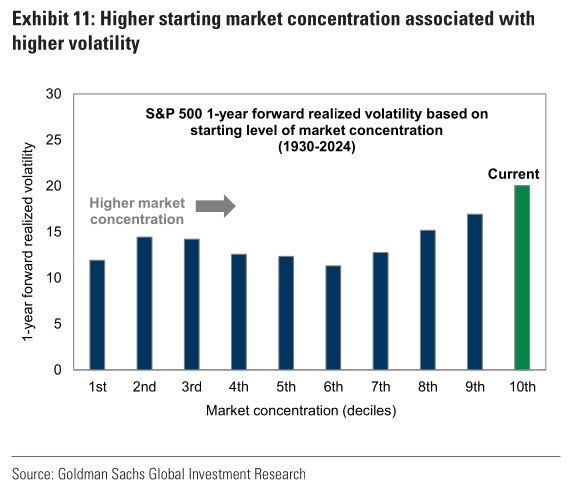

When market concentration is high, the overall index's performance is heavily influenced by the fortunes of a few companies. This dynamic can lead to greater volatility in the market, as the risk associated with these top stocks becomes more pronounced. In fact, historical data show that higher starting market concentration is typically associated with greater realized volatility over the following year.

However, volatility alone doesn’t imply poor returns. It’s the interaction between market concentration, valuation, and growth potential that shapes long-term returns.

The Relationship Between Concentration and Returns

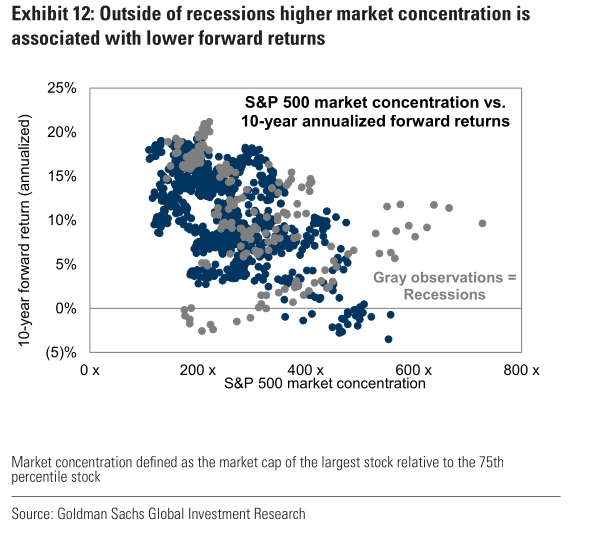

While market concentration affects short-term volatility, it has a more notable impact on long-term returns. Goldman Sachs research shows an inverse relationship between starting market concentration and 10-year forward returns.

That means that lower future returns often follow periods of high concentration, as investors may overpay for the dominant companies in a concentrated index.

The reason for this is twofold:

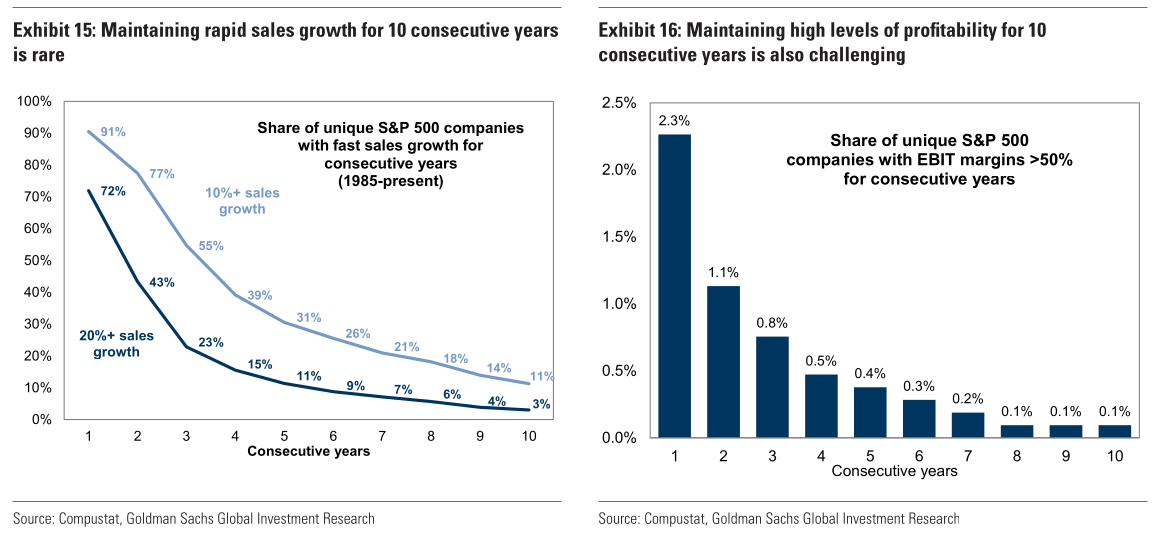

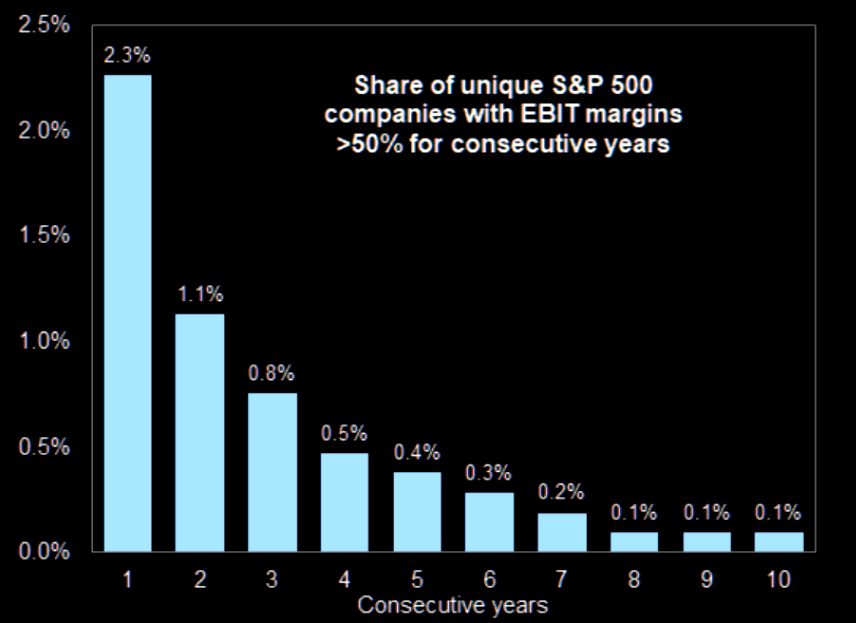

- Growth Limits: It is extremely difficult for any company to maintain high levels of growth and profitability over extended periods. Historically, even the largest, most successful companies have struggled to sustain double-digit revenue growth or maintain high profit margins for more than a decade. As growth decelerates for the largest companies, the overall index returns also slow down, given their outsized influence.

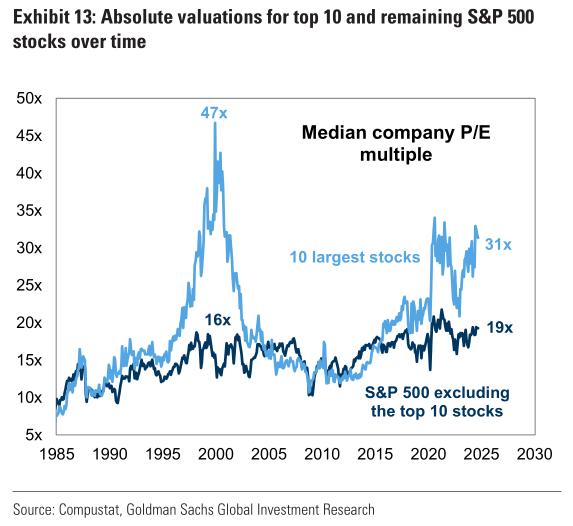

- Valuation premiums: When the largest companies in the index are trading at premium valuations, investors may not be adequately compensated for the concentration risk. In today's market, the 10 largest S&P500 stocks trade at a forward P/E of 31x, compared to 19x for the rest of the index. This valuation premium is the highest since the dot com bubble. The lack of valuation discount for concentration risk shows that investors are not pricing in a potential slowdown in growth for these companies.

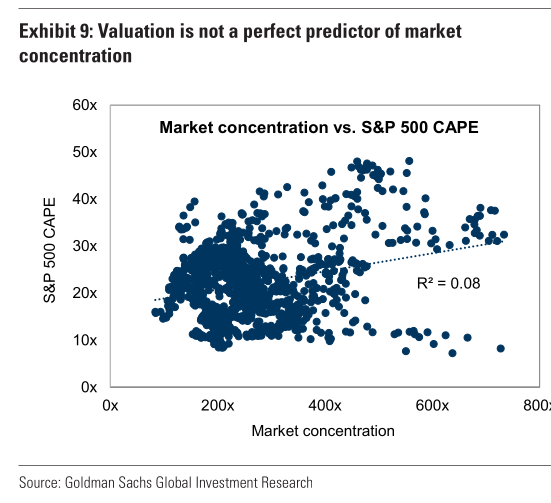

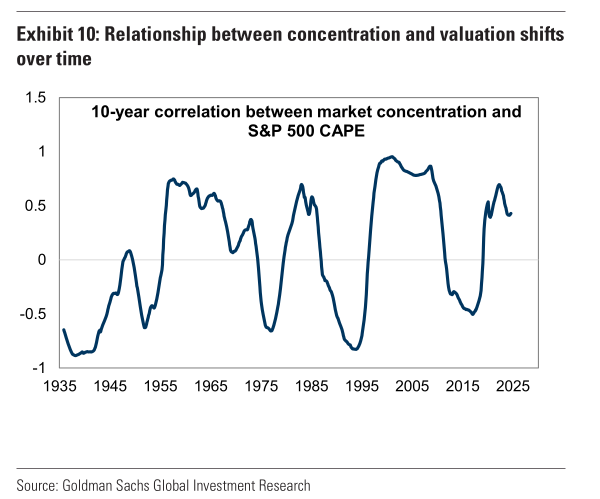

What is interesting, market concentration is not directly correlated with valuations. Only 8% of the variation in market concentration can be explained by changes in the SPX500 CAPE ratio, so other factors must be at play here.

The relationship between concentration and valuation also shifts over time, with periods of positive and negative correlation.

During the dot-com bubble and the early 1980s, concentration and valuation were highly correlated, while in other periods, such as the 1940s and 1990s, they were negatively correlated. The variability adds another layer of complexity when assessing the impact of concentration on future returns.

The "Superstar" Firm Phenomenon

The rise of the "superstar" firms, companies with scale and dominant market positions, has contributed to today's extreme market concentration. The Mega-cap tech stocks have driven the recent surge in concentration. While these companies have enjoyed high levels of growth and profitability, the question remains whether they can sustain their dominance over the next decade.

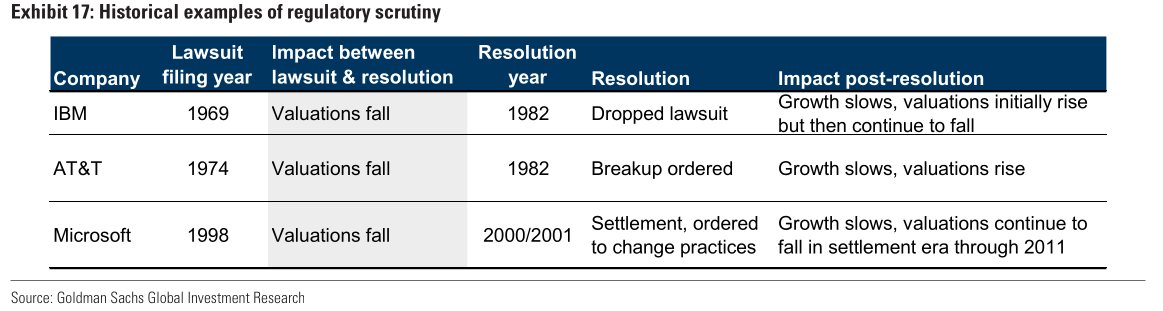

Even the most successful companies eventually face challenges in maintaining their market leadership. Government regulations, such as regulatory actions against IBM, AT&T, and Microsoft, have played a role in curbing the dominance of past "superstar" firms.

Although today's tech giants have not yet faced significant scrutiny, the risk of regulatory interventions still exists.

Economic contraction frequency

Economic contractions are periods when GDP shrinks, usually accompanied by falling earnings, lower dividends, and heightened market volatility. It's important to estimate how often such downturns happen.

Unlike some other variables in forecast model such as valuation or market concentration, which are set at the start of the return period, economic contraction frequency is the estimated for the forward 10-year period.

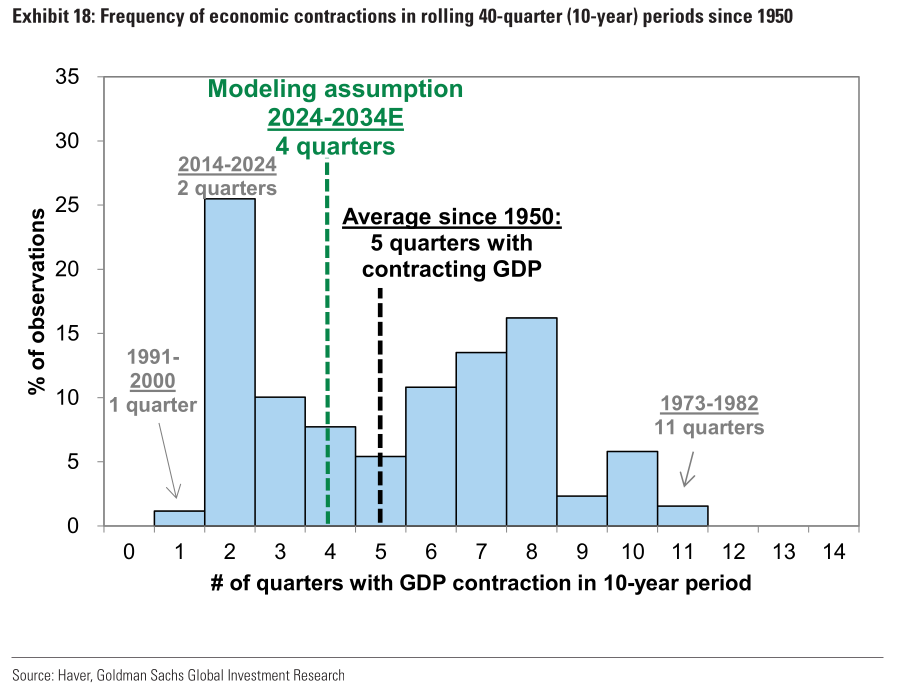

Goldman Sachs' baseline forecast assumes that the U.S. GDP will contract for four quarters over the next decade or about 10% of the time. This assumption is significantly higher than in the recent past, when the GDP contracted for just two quarters (5%) from 2014 to 2024, but it is still below the historical average of five quarters (13%) since 1950.

By choosing this middle-ground assumption, the forecast incorporated the possibility of a mild recessionary period without predicting an extreme economic downturn. However, even this modest assumption has a meaningful impact on the long-term return forecast.

Given the importance of contractions in shaping earnings and dividends, small changes in the assumed frequency of contractions can greatly impact return expectations. According to the forecast model, increasing or decreasing the assumed number of contraction quarters by just 1 would change the baseline annualized return by 50 basis points (0.5%)

for example, if GDP were to contract for only three quarters (one less than the baseline), the annualized return forecast would rise by 50 basis points, pushing the baseline return closer to 3.5%. Conversely, if GDP contracts for five quarters (one more than the baseline), the forecast would drop to 2.5%.

Historically, the frequency of economic contractions has varied. Some periods have experienced very few downturns, such as 1991-2000 decade, which saw only 1 quarter of GDP contraction. Meanwhile, other periods such as 1973 - 1982 had more severe economic stress with GDP contracting over 11 quarters over 10-year span.

Risks to GS forecast

Forecasting returns over the next decade is difficult; even the most sophisticated models cannot predict every variable. While the baseline forecast for SPX500 returns from 2024 to 2024 is 3% annualized, the actual outcome may fall above or below this estimate.

Upside risks

- Stronger economic growth: One of the biggest factors that can lead to higher than expected returns is stronger economic growth such as 1945-1955, 1973-1983, and the 1990s saw economic expansion that outpaced forecasts, resulting in stock market returns that exceeded expectations. If U.S. GDP grows more over the next decade than currently anticipated equity returns can rise above the upper end of the forecast, potentially hitting the 7% high-end scenario

- Fewer contractions: Another upside risk is a lower-than-expected frequency of economic contractions. The baseline assumption is that the U.S. economy will experience 4 quarters of contractions over the next decade. Still, returns can exceed the range forecast if the economy is more resilient with fewer recessions or smaller downturns.

- Higher valuations and market concentration persist: Valuations have tended to revert to the mean, and high market concentration has often led to lower returns. However, it's possible that today's elevated valuation multiples and market concentration can persist for longer than anyone can anticipate. Factors such as demographic shifts, the rise of tech (i.e., AI), and structural changes in the global economy can cause valuations to remain higher than historical norms.

Economic contractions are periods when GDP shrinks, usually accompanied by falling earnings, lower dividends, and heightened market volatility.

Downside risks

- Weaker economic growth: If economic growth is weaker than expected, equity returns will likely be lower than the baseline projection. Slower GDP growth would reduce corporate earnings, which in turn would drag down stock prices and total returns. That case can push returns closer to the 1% low-end scenario for the next decade.

- Overstretched valuations correct: While multiples have remained elevated since the 1990s, a mean reversion to a lower valuation level can reduce returns. Markets have struggled to maintain high valuation levels indefinitely, and if today's elevated multiples begin to fall, future returns will suffer.

- Market Concentration Normalizes: Today's market is concentrated, with just 10 stocks making up 36% of the SPX500. If this concentration begins to normalize, the performance of the index will become less dominant by a few mega-cap stocks. Returns can fall as investors reassess the risk of relying on a less diversified set of companies. High concentration often leads to greater volatility, and if investors start pricing in this risk, equity prices fall, dragging down returns.

One of the challenges for any forecast model is its ability to handle periods of rapid technological change or large economic shocks. Often, models struggled to account for events like the rise of the internet in the 1990s or major economic dislocations such as the global financial crisis in 2008. The next decade can see similar disruptions, whether through technological innovations like AI or geopolitical and economic shocks that defy traditional economic patterns.

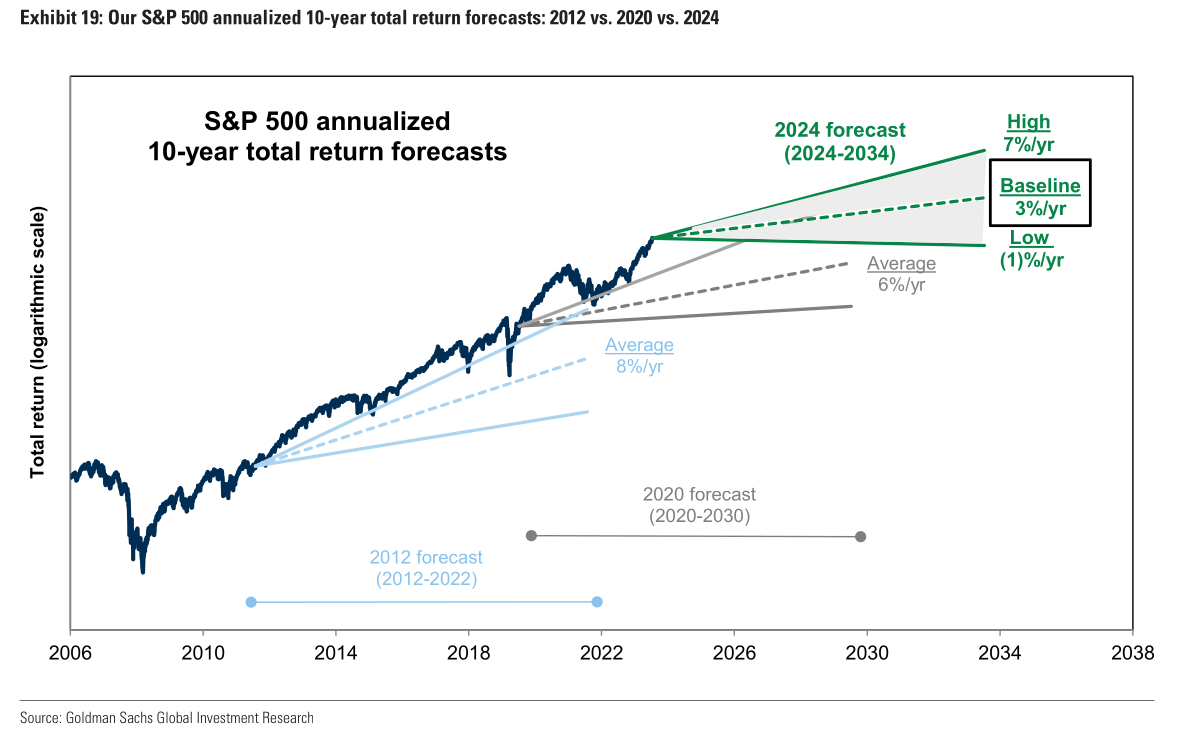

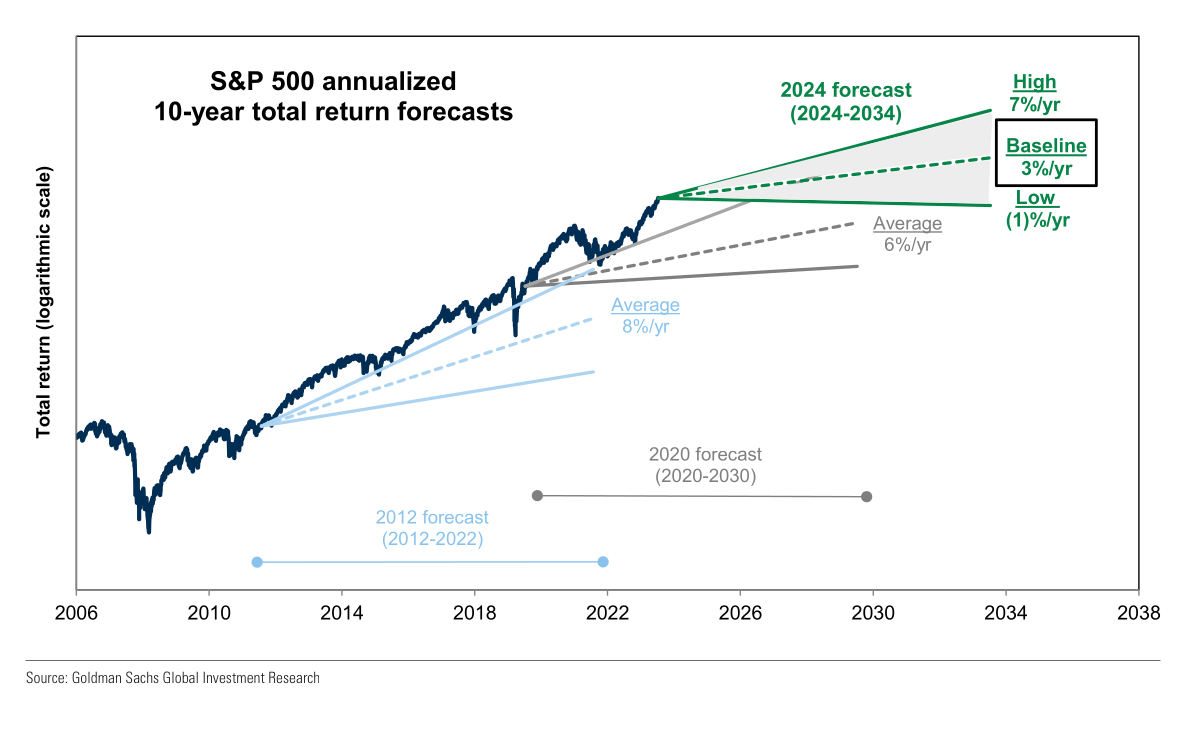

In 2012, Goldman Sachs published a report projecting an 8% annualized return of the SPX500 over the next decade. The high and low scenarios estimated 12% and 4% returns, respectively. However, the SPX500 delivered a 13.3% annualized total return from 2012 to 2022. (The average, however, they were right)

Returns exceeded expectations mainly because of stronger economic growth and fewer downturns. High valuation multiples also helped boost the market's performance. If history tells us anything, unexpected economic strength, and ongoing high valuations might result in a similar positive surprise in the next decade.

While the baseline forecast for the SPX500 returns over the next decade is 3% annualized, many factors can cause actual returns to deviate from this estimate. Upside risks such as stronger economic growth, fewer recessions, and persistent high valuations can push returns higher, potentially reaching a 7% high-end forecast. On the downside, weaker growth, declining valuations, and a normalization of market concentration can result in much lower returns, closer to the 1% low-end scenario.

Relative Performance of Equities: What Investors Should Expect vs. Bonds and Inflation

When forecasting long-term returns for the SPX500, it's important to consider not only the absolute returns but also the relative performance of equities compared to other asset classes, particularly bonds and inflation.

Goldman Sachs model shows that U.S. equities are likely to face headwinds over the next decade, with higher-than-usual probability of underperforming both bonds and inflation.

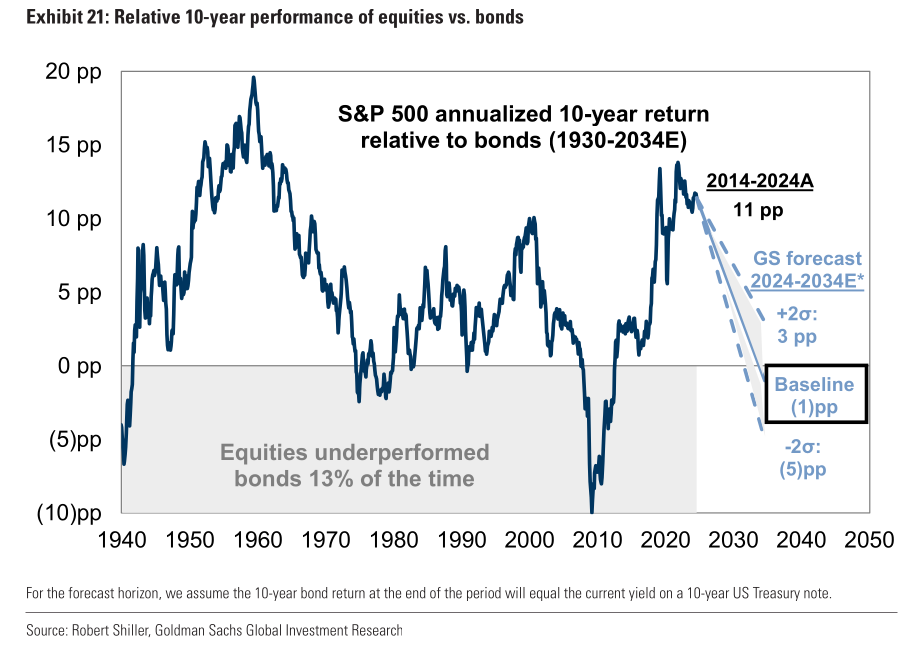

Equities have outperformed bonds in most 10-year periods, but the coming decade may look different. GS model implies a 72% probability that the SPX500 will underperform bonds over the next 10 years.

That marks a significant departure from the past where equities have only underperformed bonds 13% of time since 1930.

Factors that contribute to this elevated probability

Valuation levels: The SPX500 trades at historically high valuation multiples, which implies lower forward returns. Meanwhile, the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds is relatively high (4%) compared to its historical average, making bonds a more attractive alternative in the near term.

Market concentration: Today's market is highly concentrated, with a small number of large-cap stocks dominating the index. This reduces diversification and increases volatility, further dampening equity returns relative to bonds.

As a result, the baseline forecast suggests that equities will underperform bonds by 1 percentage point per year over the next decade, ranging from +3 percentage points to -5 percentage points depending on market conditions.

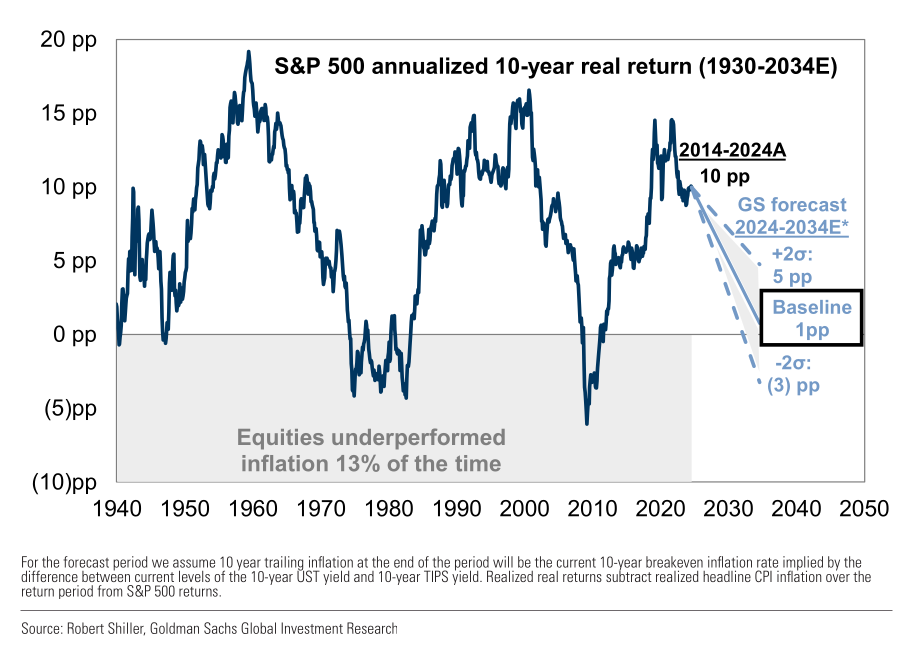

While the probability of equities underperforming bonds is high, the outlook for equities relative to inflation is more favorable. The model forecasts a 33% chance that equities will underperform inflation over the next decade, more than double the historical rate of 13%

The baseline forecast implies that equities will outperform inflation by 1 percentage point annually, assuming inflation runs at the currently implied 2.2% for the next 10 years. However, this outperformance is modest by historical standards, and the range of potential outcomes is wide.

- High-end forecast: Equities could outperform inflation by as much as 5% points per year, reflecting a strong economic environment with low inflation and solid corporate earnings growth.

- Low-end forecast: On the downside, equities could lag inflation by 3 percentage points, occurring when inflation rises sharply, eroding real returns.

One key variable affecting both absolute and relative returns is market concentration. The dominance of a few large-cap stocks in the SPX500 today has increased the risk associated with equities. If we exclude market concentration from the forecast model, the annualized 10-year return for equities jumps from 3% to 7%, reducing the probability of underperformance relative to both bonds and inflation.

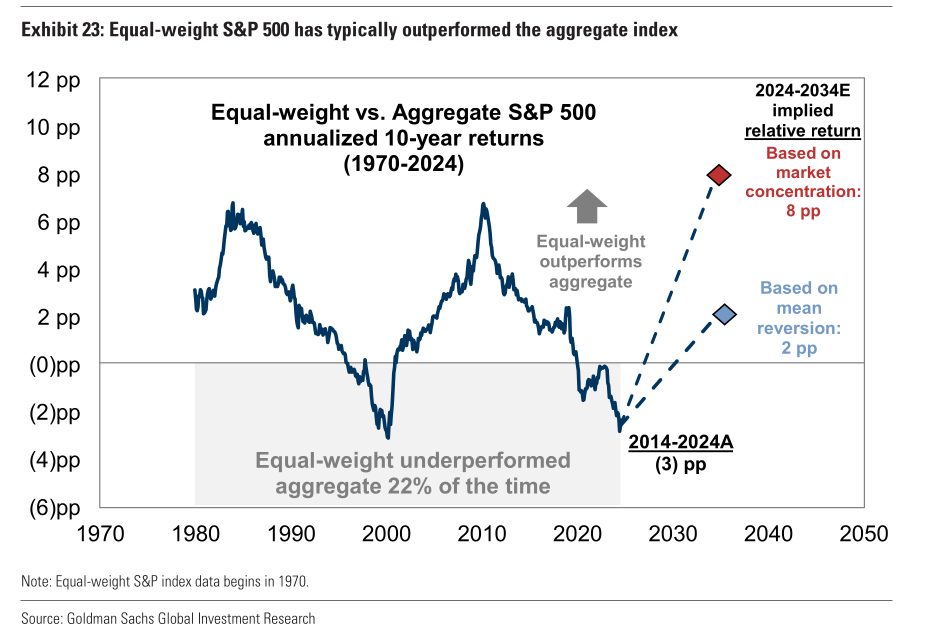

Why the Equal-Weight S&P 500 May Outperform

One key question in equity investing is whether the equal-weighted S&P500 (SPW) will outperform the aggregate market-cap-weighted S&P500 (SPX500).

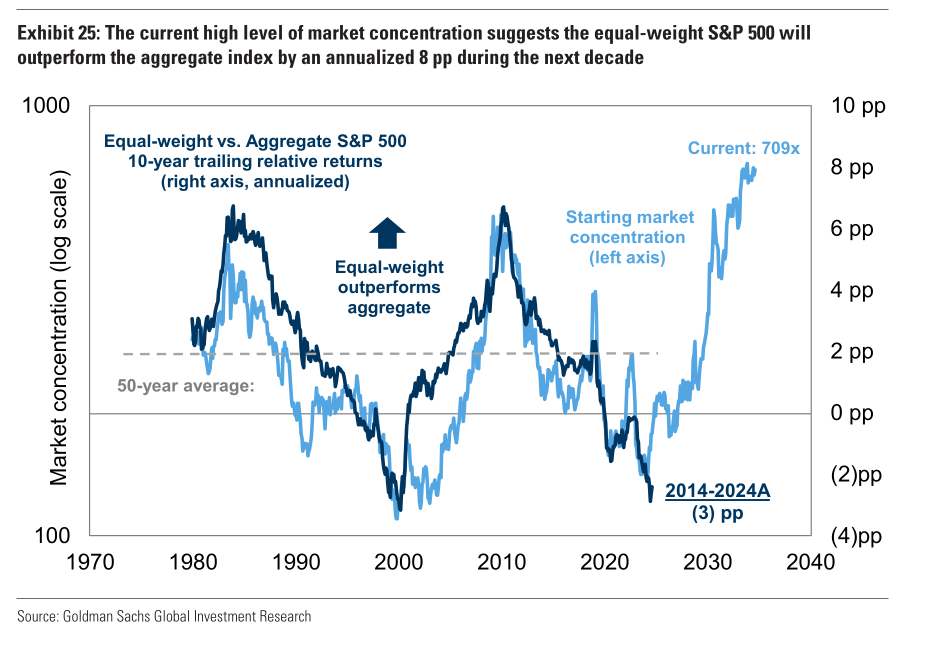

The equal-weight S&P500 has tended to outperform the aggregate index over rolling 10-year periods. Since 1970, the equal-weight benchmark has outperformed the aggregate index 78% of the time, delivering an average annualized performance of 2 percentage points (pp). However, this pattern has been disrupted in recent years.

This recent underperformance reflects the extreme dominance of a few mega-cap tech stocks, which have driven the performance of the aggregate index. The tech and AI boom has led to sharp gains for these companies, heavily tilting the cap-weighted index in their favor. However, the equal-weight index could come back as market concentration eventually normalizes.

Role of Market Concentration

Market concentration is one of the most important drivers of the relative performance between the equal-weight and aggregate indices. When market concentration is high, as it is today, a small number of large companies dominate the index. That reduces the aggregate index's diversification benefits, while the equal-weight index gives smaller stocks a larger weight, which tends to outperform.

The sharper periods of outperformance for the equal-weight index followed peaks in market concentration. For instance, during the 1973 - 1983 period and 2000 and 2010 period, the equal-weight index outperformed the aggregate index by 7pp annually. These periods do coincide with a decline in the dominance of large-cap stocks, allowing smaller companies to drive index returns.

Today's market is more concentrated than ever, with the top companies making up 36a% of the total market capitalization of the S&P500. The extreme concentration is in the 99th percentile, and we may be on the cusp of another period where the equal-weight index outperforms.

Goldman Sachs analysis implies that given the current level of market concentration, the equal-weight index could outperform the aggregate index by as much as 8pp annually over the next decade. While this scenario represents an extreme case, an even more modest mean reversion would imply 2pp of annualized outperformance for the equal-weight index.

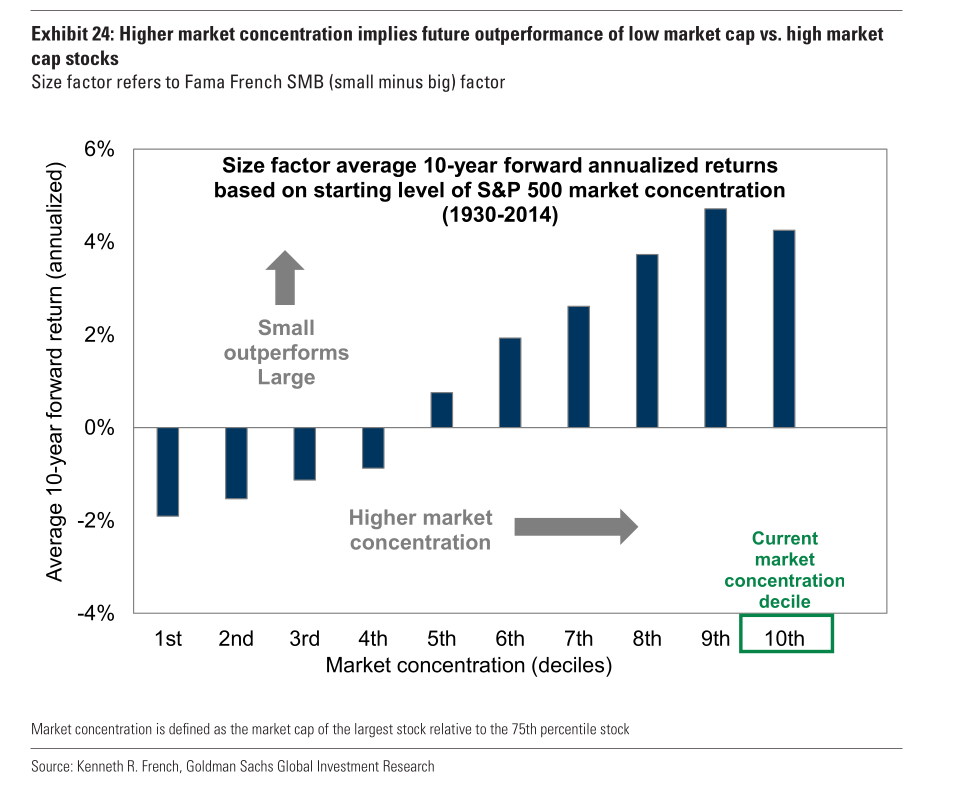

The Size Factor: Why Small Stocks Outperform

The equal-weight index's outperformance is closely linked to the size factor, which refers to the historical tendency for small-cap stocks to outperform large-cap stocks. When market concentration is high, small stocks tend to generate higher returns relative to their larger counterparts.

Exhibit 24 shows that when market concentration is in its highest deciles, the size factor delivers average 10-year forward returns of 4% annually.

Given today's extreme market concentration, smaller-cap stocks will likely outperform their large peers, contributing to stronger relative performance for the equal-weight index. The relationship has historically been asymmetric, with small-cap stocks delivering stronger outperformance during periods of high concentration than underperforming during periods of low concentration.

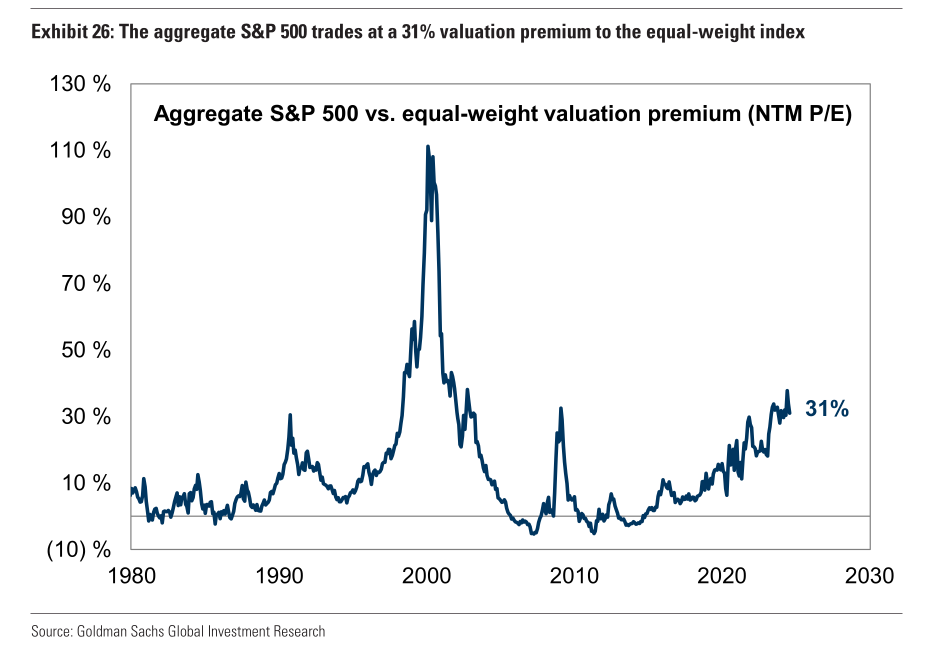

Valuation premium and future returns

Another factor favoring the equal-weight index is the valuation premium between the aggregate and equal-weight indices. The aggregate S&P500 (SPX) currently trades at a 31% premium to the equal-weight index (22x forward P/E for the aggregate vs. 17x for the equal-weight). This premium has risen significantly over the past decade, reflecting the outsized gains of mega-cap stocks.

While the relationship between the valuation premium and future returns is not perfectly correlated, periods of large valuation spreads have historically been followed by stronger relative performance for the equal-weight index. The current valuation gap could be a sign for future equal-weight outperformance.

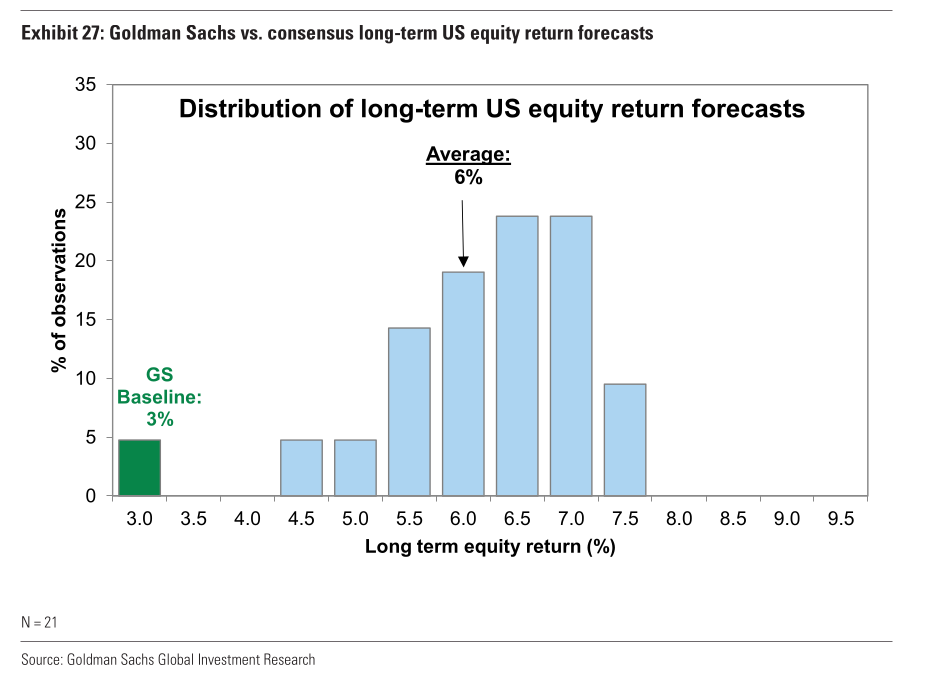

How does GS's Long-term equity return forecast compares with consensus

Goldman Sachs is notably more cautious than the broader market consensus. Goldman Sachs predicts a 3% annualized return for the S&P500 over the 2024 - 20234 period, which is lower than the 6% consensus average of the asset managers.

The consensus forecast for long-term U.S. equity returns from 21 asset managers ranges from a low 4.4% to a high 7.4%, with an average of 6%. By contrast, Goldman Sachs's baseline forecast of 3% sits below the entire range of consensus estimates. Even the most optimistic asset managers in the survey expect returns well below the historical average for the S&P500, which has delivered 11% annualized returns since 1930.

Goldman is even more conservative when compared to the returns of the past decade, where the S&P500 delivered a 14% annualized return from 2014 to 2024. While most consensus anticipates lower returns than in the past, the GS model paints a more pessimistic picture of future equity performance.

Reasons as explained before

- Valuations are elevated: The S&P 500 currently trades at historically high valuation multiples, particularly the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) ratio. High starting valuations typically lead to lower forward returns.

- Interest rates: The yield on 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds is relatively high at around 4%, compared to lower levels seen over much of the past decade.

- Market Concentration risks: High concentration increases the risk of volatility and underperformance if these large companies face challenges.

- Economic growth concerns: lower GDP growth would dampen corporate earnings and, by extension, stock returns

Even though GS's forecast is more conservative than the consensus, most asset managers also expect lower-than-average returns on U.S. equities over the next decade.

- Starting valuations: Many asset managers acknowledge that today's elevated valuation will weigh on future returns. When stocks are expensive relative to earnings, their upside potential is limited.

- Interest rates: As bond yields rise, the risk-adjusted return on equities becomes less attractive, leading to lower expected equity returns

- Structural Shifts: Some consensus forecasts factor in long-term structural changes in the economy, including technological advancements, demographic shifts, and global trade dynamics.

Are Pension Plans Too Optimistic About Future Returns?

As corporate and public pension fund plans for the future, their long-term return assumptions are critical for ensuring they can meet their obligations for retirees. However, Goldman Sachs' 3% annualized 10-year return forecast for U.S. equities suggests that many pension plans may be too optimistic about the future performance of their investments.

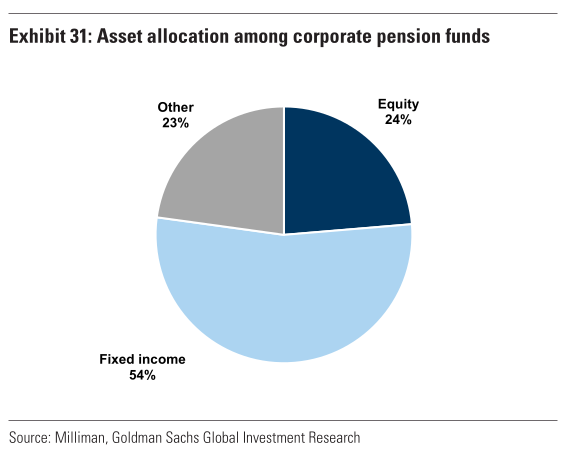

Corporate Pension Funds

Corporate pension plans, on average, assume a 6.1% long-term return on their assets. This assumption is based on a diversified portfolio that includes equities, fixed income, and alternative investments. While corporate pension plans are usually more conservatively allocated than their public counterparts, only 24% of their portfolios are in equities. The vast majority of these plans are assuming returns far above Goldman Sachs' 3% equity forecast.

Although this may seem concerning, the risk of a shortfall is somewhat mitigated by corporate pension plans being nearly fully funded, with funded ratios averaging around 100% as of the end of 2023. That means that even if returns come in below expectations, these plans may still be able to meet their obligations to retirees without requiring additional contributions from employers.

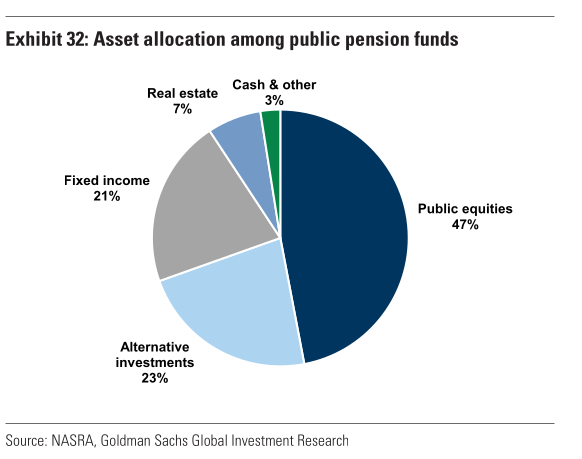

Public Pension Funds

On the other hand, public pension funds are even more optimistic, assuming an average return of 6.9% on their assets. Unlike corporate pension plans, public pension funds allocate a larger share of their portfolios (47%) to equities, which exposes them to greater risk if equity returns fall short of expectations. Given Goldman Sachs' forecast of 3% annualized returns for U.S. equities, public pension funds may struggle to achieve the returns they need to meet their future obligations.

None of the 131 public pension plans surveyed have a return assumption as low as Goldman Sachs' forecast for U.S. equities. That's concerning, many public pension plans could face funding shortfalls in the year ahead, especially if their equity-heavy portfoiios fail to deliver expected returns.

Both corporate and public pension funds rely on a mix of asset classes to generate the returns needed to fund future retiree benefits. However, if U.S. equities perform as Goldman Sachs predicts, other asset classes will need to step up to fill the fap.

Fixed Income: Yields on 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds are around 4%, while investment grade bonds offer 4.8% and high yield bonds yield 7%. These returns are not substantially higher than GS equity forecast, meaning that fixed income alone isn't enough to close the gap

International equities: Non-U.S. equities may offer higher returns. However, since U.S. stocks account for 65% of the MSCI All-Country World Index, international stocks would need to outperform U.S. equities to compensate for the shortfall significantly.

Alternative investments: Private equity, private credit, and real estate can provide higher returns, but these assets also carry higher risk and may not deliver the consistent returns needed to offset lower public equity performance.

Goldman Sachs predicts that U.S. stock returns will be lower than many pension funds expect. Corporate pension plans have some protection since they use safer investment mixes and are well-funded. However, public pension funds rely more on stocks and have more aggressive return goals.

If investment returns do not meet their expectations, pension plan leaders, advisors, and managers might face issues in the coming years. They may need to rethink their return assumptions and consider different strategies.

Notable comments

Yardeni: "The forward P/E is relatively low compared to the forward P/S because the S&P 500 forward profit margin has been rising into record-high territory and should continue to do so in our Roaring 2020s scenario"

Goldman: "Maintaining high levels of profitability for 10 consecutive years is also challenging"

"With the Buffett Ratio (i.e., forward price/sales, or P/S) at a record-high 2.9 and the S&P 500 forward P/E elevated at 22.0 times, we agree that valuations are stretched by historical standards"

"S&P 500 earnings per share has grown roughly 6.5% per year for nearly a century. Assuming 6.0% growth over the coming decade (and removing dividends from the equation), valuations would need to be halved to produce annual returns of just 3% that Goldman speaks of"

Yardeni is much more optimistic on the US economy.

"In our opinion, even Goldman's optimistic scenario might not be optimistic enough. That's because we believe that the US economy is in a "Roaring 2020s" productivity growth boom with real GDP currently rising 3.0% y/y and inflation moderating to 2.0%."

And therefore also much more optimistic on the stock market.

"If the productivity growth boom continues through the end of the decade and into the 2030s, as we expect, the S&P 500's average annual return should at least match the 6%-7% achieved since the early 1990s. It should be more like 11% including reinvested dividends."

Become a Premium member. Premium newsletters & Discord community access

Join Discord to get the full value out of the newsletter. There's no extra cost associated with Discord. Yes, options data, such as dark pools, options gamma, unusual flow, etc., are also included. Also, educational content, reports, and direct questions to me, and often, I share my trades & thoughts in real-time as the market moves.

However, I want you to understand rather than copy a trade.

Become a premium member. Besides crypto, if you cashed out a lot or are planning. I highly recommend the "stocks" and "fixed-income" channel sections for long-term plays and wealth-building